As the recently unified Kingdom of Italy struggled to stabilise the economic conditions in Southern Italy, a great wave of emigration took place, and from the 1880s until well into the 20th century millions of these emigrants would arrive in the United States of America. For many the 'Land of Opportunity' brought promises of prosperity which they could share with their family back in Italy, while for others it represented a new life—an opportunity to make a name for themselves in their chosen field.1

Among these new arrivals, many brought with them a love of fencing, both as a professional pursuit and as a healthy pastime. Masters such as Filippo Brigandi, Pietro Lanzilli, and Leonardo Terrone are a few of the many names that would represent the Italian school of fencing in the USA at some point during this period (for better or worse), but one Italian fencer of this era whose name is perhaps among the most well-known in the historical record is Generoso Pavese, due in no small part to the fact that he published a fencing treatise in 1905 entitled Foil and Sabre Fencing.2

A great advantage that this treatise had for the Anglophone world of fencing was that for a long time it was the closest thing to an English translation of Masaniello Parise's acclaimed 1884 treatise Trattato teorico-pratico della scherma di spada e sciabola, the regulation fencing text of the Italian military at the time. Pavese was an avid proponent of this tradition, claiming to be a world fencing champion and a graduate of Parise's military fencing master's school.3

However, as I will demonstrate, this image of Pavese as a revered fencing master and competitive champion quickly begins to crumble once its foundations are examined. In this article I will address each aspect of Pavese's professional life and the factual claims made by or about him, where the ability to verify said claims exists, and attempt to redefine his place among the figures of Italian fencing in this period.

American Debut

According to his 1898 certificate of naturalisation, Pavese claims to have arrived in the USA on 16 May 1891, but this date is later contradicted by his passport application from 1905, which gives his arrival date as 29 April 1892; this latter year will be what is more commonly listed in subsequent state and federal censuses. The 1905 passport application states Pavese was born on 30 January 1865 in Vallata, Italy, which is corroborated by his own treatise, but which also claims he arrived in 1893 on the occasion of the Chicago world's fair.4

Despite these earlier dates, the first mention I have been able to find of Pavese is in late 1893, appearing as a guest at a couple of fencing exhibitions in New York held in honour of the famous Italian fencing masters Eugenio Pini, Agesilao Greco, and Carlo Pessina, who had been touring the country holding exhibitions and challenging local champions. Generoso Pavese and Luigi Sfrisi are said to be Italian army officers, neither presenting any challenge in their bouts against the likes of Pini and Greco. In the Italian fencing magazine Scherma Italiana, neither Pavese nor Sfrisi are so much as given even an honourable mention in its reporting on these events.5

It is only after Pini, Greco, and Pessina have left the country that Pavese begins to receive individual attention from the American press. As early as February 1894, only a few weeks after the Italian masters departed, Pavese had begun challenging various east-coast fencers and organising public contests, with the Brooklyn Daily Eagle calling him the 'champion of Italy'.6 Another article promoting the same event claims Pavese is a student of one 'Pessini' (likely Pessina), the 'recognised champion swordsman of the Italian army in Italy'.7 Following this event, one newspaper says that Pavese was 'formerly a lieutenant in the Italian army, but is now a shoemaker in Newark'.8

In May of that same year, Sfrisi too is named the 'champion of Italy' in a Connecticut newspaper promoting his upcoming exhibition against fencing master Etienne Postel and amateur Helen Englehart.9 While Sfrisi does not appear in any subsequent events in America (he would eventually return to Italy and continue to teach fencing), for Pavese the year 1894 would be the start of over a decade of challenges and public contests all across the United States, seeking out publicity wherever he could.

European Champion

America would be home to many other self-proclaimed masters and champions from Europe aside from Pavese (subjects for future articles, perhaps), but none ever received quite so much media attention as he. The 1890s would be a particularly popular time for these pretenders, and not just those hailing from Italy. Newspapers throughout the country advertised public contests involving 'champions' of America, England, Germany, Russia, and France, many of whom Pavese would encounter at some point in his career.

Aside from the aforementioned Sfrisi, another person declaring himself the 'Italian champion' in 1894 was one Greco Martino. Having seen Pavese's claims of being the champion of Italy, Martino had a letter of his published in New York's National Police Gazette proclaiming that he was the 'legitimate' champion of Italy, having held the title for 8 years, and that not only was Pavese a fraud, but Martino had never even heard of him before. He challenged Pavese to a contest, claiming he can defeat him in only 10 minutes, but it is unclear if this ever eventuated.10

Needless to say, none of these three men had ever held a 'championship' title in Italy, nor did any such title even exist. Not only that, but no competitive record can be found for either Pavese or Martino; Luigi Sfrisi is the only one of these three with any verifiable background in Italy. What is known about Sfrisi's career up to this point is that he was a sergeant and fencing instructor at the cavalry normal school in Pinerolo before attending Parise's military fencing master's school in 1885, and that he was classified in the second category for masters in both sabre and foil at the 1891 Bologna tournament.11

As for Pavese, a later article claimed that he had performed excellently at the Florence 1887, Rome 1889, Bologna 1891, and Venice 1891 tournaments,12 and the preface to his own treatise claims:

During the years 1889, 1890, 1891 and 1892 he attended and took part in all the principal fencing tournaments in Italy, France, Spain and Austria, and gained distinguished honors at his every appearance.13

Most of the major tournaments in this period are well-documented in newspapers and sporting magazines, particularly in France and Italy, and sometimes a tournament committee would publish their own report with a comprehensive list of competitors and their results. The cited tournaments of Florence (1887), Rome (1889), and Bologna (1891) were particularly significant tournaments at the time, and so although their mention suggests Pavese was well-informed of the Italian competitive scene, his name is absent from all the articles and reports that discussed them.14

Even the renowned French masters Mérignac, Prévost, and Rouleau are specifically listed as having been defeated by Pavese on a trip to Paris along with Eugenio Pini in 1892.15 This claim came to the attention of the French newspaper Le Journal, commenting that they do not recall having ever seen Pavese in Paris, and that if he had indeed defeated all these masters, it would have been highly publicised.16

In January 1905 Mérignac came to New York to give an exhibition, inviting all local fencers to take part, Pavese included.17 Having taken issue with Pavese's claiming to have defeated him in the past, Mérignac singled out him as soon as he arrived in the country, with both supposedly agreeing to a challenge of two 20-minute sabre bouts and two 20-minute foil bouts to decide world championship.18 It does not seem like this challenge ever took place, and Pavese did not attend the exhibition in New York, with the Boston Globe saying he had 'engagements elsewhere' and sending his student Count Magnoni in his place.19

The only tournament outside of America I have been able to find Pavese taking part in was during his trip to Europe in 1905. At an international foil tournament in Paris, Pavese was eliminated in the first round by a French military fencing master named Molinié, who would end up in 6th place.20 Mentions can also be found of small exhibitions organised by Pavese in Italy in the same year, but he seems to have avoided the all the other tournaments which took place around the continent during that time.21

Duellist

The image of a seasoned duellist, ever-ready to heroically defend his honour by the sword, is a significant part of how Pavese promoted himself in America. Italians in general already had an international reputation for a 'fiery temperament' by this time, and Pavese seemed happy to play along with this stereotype, challenging his American opponent to a duel if a particular bout was not judged in his favour, or even just as an alternative to a contest with blunt weapons.22 In a brief yet enthusiastic report of a public exhibition of his in 1896, the Boston Post wrote:

Brave men who are skilled in handling the foils would accept an insult rather than challenge this man to an encounter. Pavese has had many a battle, and could tell some thrilling stories, many of them having a coloring of love. His career has been romantic, and he has to stop and think before he can tell you the number of duels he has fought.23

In the first few days of the Spanish-American War, Spanish naval attaché (later revealed to be a spy) Lieutenant Ramon de Carranza challenged General Fitzhugh Lee and Captain Charles Dwight Sigsbee to a duel after the latter two accused Spain of blowing up the USS Maine.24 Recognising an opportunity for celebrity, or perhaps even out of genuine patriotic zeal for his adopted homeland, Pavese responded to this challenge on behalf of Lee and Sigsbee with a letter published in the New York Evening Journal.

The accompanying article describes how Pavese has fought in a number of duels, emerging victorious each time, citing duels with a Rodriguez in Madrid, Count Cotini of Aversa, a Cardacci of Naples, a Fiorontini of Belgium, and Giuseppe Grasso of Parma.25 Whilst this list of specific names and locations lends an air of credibility to Pavese, there are a couple of underlying issues with his story.

Firstly, although he states in his letter his desire that the 'challenge issued by you [Carranza] to General Lee and Captain Sigsbee should not go unanswered', there had been multiple other gentlemen putting their names forward publicly as replacements for Lee and Sigsbee weeks before Pavese did (with no reply from Carranza).26 Secondly, although some of the names listed in the article from the New York Evening Journal would reappear in future media attention around Pavese (who certainly did not miss an opportunity to recount his challenge to Carranza), the details surrounding his prior duels and the Carranza affair itself would become more dramatic and change in future retellings.

An article from the Denver Evening Post in 1899 highlights how quickly this mythology would develop. It claims Pavese had had 'something like twelve duels', with two of them being fatal for his opponent; he is said to have thrust Martinez through the chest in Barcelona in 1887, and 'Cardac' was stabbed through the heart in Madrid in 1888. It then gives an elaborate account of how his duel with Count Cotini came about, even requiring the Italian minister of war to give his personal approval to 'fight for the honor of the regiment.'27 The article says the duel took place in November 1898, but given that Pavese had long been in the USA by that time, this was probably meant to be 1888. The minister cited is Cesare Ricotti-Magnani, and while he did indeed serve as Italian minister of war several times, he was not the acting minister of war in either 1888 or 1898.28

A recurring theme in the retellings would be his two fatal duels against Frenchmen, with the aforementioned Cardac/Cardacci, supposedly a famous French fencing master, being the most commonly mentioned (albeit with several spelling variants), but the chronology, locations, and total number of duels were inconsistently recalled.29 Whilst the number and nature of the duels attributed to Pavese are not unprecedented in the period, the unverified participants and the deaths of two make the narrative extremely unlikely. Despite the frequency of duels themselves, it must be noted that duels which resulted in death were a rarity in Western Europe by this time, and were thus always subject to avid media coverage, particularly if the one who died was a famous French fencing master, as Pavese claims.30 No record can be found of any duels in which Generoso Pavese was involved, nor any of the supposed victims.

Regardless of how true Pavese's duelling past was, his characteristic hot-headedness seemed to be largely beneficial to his reputation. It was through this eagerness to hand out duelling challenges that he would end up meeting President Theodore Roosevelt in 1903, who was supposedly impressed by Pavese's chivalric conduct when he challenged the French fencing masters Lucien Mérignac and Alphonse Kirchhoffer to a duel when the French press claimed the latter two convincingly defeated their respective opponents, Francesco Pessina and Franco Vega, in a duel in December 1902. It is hard to know if the Frenchmen actually received their challenge from Pavese, or even cared, but the result was that Pavese was given an opportunity to meet with the U.S. President, and was for some time said to be his fencing master—a story which caught the attention of both American and European newspapers.31

As for the Carranza affair, some articles would claim that Pavese travelled to Canada to personally challenge Carranza to a duel, which he refused, even attempting to follow the Spaniard back to Madrid.32 As with the others, no record can be found of this duel taking place, and passports and passenger listings can be found under his name which indicate that the first time he left the American continent since his arrival was his aforementioned trip to Europe in 1905.33

Military Fencing Master

Along with his self-given title of 'champion of Italy' and later 'world champion', from early on many newspapers also referred to Pavese as a 'professor', a title commonly used in English for fencing masters.34 As there were no federal governing bodies for the title of fencing master in America at this time, it could take as little as declaring yourself a fencing master or giving lessons on a regular basis to be considered as such. Italy, on the other hand, had a much more established culture for the certification of fencing masters—especially within the military, where Pavese is said to have earned his qualification.

In the preface of Pavese's treatise it states that he joined the military voluntarily, serving in the 19th cavalry before being accepted to the internationally-renowned military fencing master's school in Rome, then returning to his old regiment as a fencing master after graduating.35 A similar background is given articles from the Washington Times and Baltimore Sun, with the former saying that he was the fencing instructor of the 19th cavalry for eleven years, and the latter that he attended the school from the age of 16 to 27, acting as the fencing master of the 19th cavalry for only some of that time.36

Contrary to all this, however, in a feature article on Pavese in the New York Sun from 1903, it claimed that at the age of seventeen Pavese entered the 'instruction platoon' (i.e. the cavalry school) in Pinerolo, where his talent for fencing was noticed, resulting in him being admitted to the Rome fencing master's school in 1885. After graduating in 1887 with honours, he 'remained there until 1887 [sic] when he was ordered by the Italian Government to leave school and join his regiment—the Ninth Cavalry.' The same article says that while Pavese was at the school he was fortunate to have studied under 'three of the best swordsmen ever known: Professors Carlo Pessini, Doni and Peresi'.37

The first of these names refers to Carlo Pessina, a prominent instructor at the school, and the third is likely meant to be Masaniello Parise, the school's director. The second of the three, likely one Vittorio Doni, was indeed a military fencing master, but he is not known to have been teaching there at the time, albeit he did attend a 4-month course at said school in the first half of 1885, after which he would have returned to teaching in his regiment, coincidentally the 19th cavalry.38 It will also be remembered that the aforementioned Luigi Sfrisi was teaching at the Pinerolo cavalry school in 1885, so it is possible that Pavese has some history with him too.

While it is conceivable that Pavese could have taken part in the entrance exam, there is no evidence to suggest that he ever attended the military fencing master's school and subsequently graduated. Lists of the people who were accepted into the school were published in the official military journal, as were the start and end dates of its courses. He also cannot have been a student at the school if articles from December 1893 were correct in stating that he was an army officer, as only sergeants were admitted.39

Nor did the unverified claims about his military service end after his time Italy. On his death, obituaries in the New York Times and Baltimore Sun say he served as a cavalry captain under Teddy Roosevelt in the Spanish-American War, with the two being 'close friends'. This is, unsurprisingly, entirely unsubstantiated, with the 1930 federal census clearly stating 'no' in the column marking veteran status of the U.S. navy or military.40

While evidence indicates that he was never a qualified military fencing master in his native Italy, it is not unlikely that Pavese was involved in the military to some degree, perhaps training at the Pinerolo cavalry school, given his recognised ability for horse riding, as shown in various mounted tournaments throughout his career, and his constant desire to associate himself with military pursuits. This desire manifested itself even in his later life, when he founded a Fascist youth 'military school' in Baltimore in the late 1920s, modelled after the 'Balilla' organisations of Fascist Italy.41

Unlike Pavese, a Florentine civilian fencing master named Marco Piacenti did have an established competitive reputation throughout Europe first as an amateur, then becoming a master in 1898. Shortly after this he moved to Boston, where he would teach at the local athletics club for a few years before returning to Italy.42 As someone who was very active in the fencing scene the same time as Pavese claims to have been, Piacenti would be in perfect position to verify Pavese's integrity and merit as master, but this he never did. On the contrary, in an 1899 article by Piacenti published in the Boston Sunday Post, he denounces the 'self-styled fencing teachers' who come to the USA looking to profit off their lies, as well as giving a plausible reason as to why this phenomenon was so prevalent at the time:

Fencing in North America is without doubt the branch of sport which is least valued here, and the cause of this is that there have come to this country a great number of self-styled fencing teachers who have adopted a method that is neither the French nor the Italian method, and which has disgusted many Americans with fencing altogether, as they have not had a chance to see its artistic side. In fact while we see hundreds at a fencing tourney in Italy or France only about twenty amateurs will come together at such a tourney in a great city like Boston.

The reason is that the persons who come to this country have no profession, and in order to make their living begin to teach fencing, of which they do not know the first rudiment.

In this first year of my teaching in Boston I have seen people with a very good disposition for fencing and also with a very fine constitution for this sport, but they had been spoiled by their former teachers.

[...]

I sincerely hope that a good fencing teacher, Italian or French, will soon come to this country, and that this highly interesting sport will then eagerly be taken up by those who now take no interest in it.43

American Champion

It would be a whole other article in itself to thoroughly address Pavese's competitive career in the USA, so for this article it will suffice to demonstrate how his lack of credibility regarding other aspects of his life also manifested in this realm. From late 1894 until the late 1910s, Pavese insistently promoted himself as 'champion of the world' (and, later, that he remained undefeated) at a time when several others in the USA were also giving themselves the same title.

American news media were, by and large, happy to entertain these claims even in spite of several public defeats and withdrawals on the part of Pavese. In April 1894 a contest between Pavese and the multi-talented sportsman Duncan C. Ross ended early when enraged Italian spectators stormed the stage to protest perceived bias from the referee in favour of Ross. The two would meet at least twice more in the future, both times with the match ending prematurely in similar circumstances.44

In March 1897 Pavese was decisively defeated by an Italian fencing master named Francesco Scannapieco in Philadelphia, but again he would continue to proclaim his title as world champion, denying his defeat by Scannapieco.45 A defeat that received more publicity took place in San Francisco in 1899 against the French master Louis Tronchet, with the hot-headed and outraged Pavese declaring 'his willingness to meet Tronchet in mortal combat in Montreal or Mexico'.46

None of this is to say that Pavese was a particularly bad fencer, at least by American standards. Pavese taught and successfully fenced in public for over a decade, earning the admiration of many; however, given that some of the public bouts occurring this time involved prize money of up to $1,000 for the victor (over $30,000 in today's money), anyone's public boasting of American or world championship or of being undefeated should, as a default, be taken as little more than self-promotion for the sake of profit.

The Treatise

So with all this said—having thoroughly demonstrated that not only did Pavese lie about his background and career, but inconsistently so—what does this mean for his treatise? While Pavese himself says he drew from from Masaniello Parise's 1884 treatise Trattato teorico-pratico della scherma di spada e sciabola to some degree, the fact that Pavese likely did not attend the Parise's military fencing master's school in Rome means that any additions or original insights that may be found in his book cannot be assumed to derive from what was taught at said school. However, since nothing is yet known about Pavese's fencing experience during his time in Italy, it cannot be said for sure that he was not taught Parise's method.

If Pavese did grow up in the Naples area, it is certainly possible that he could have received lessons from Masaniello Parise prior to his appointment to the Rome school or any other member of the Parise family of fencing masters who were active during Pavese's youth. In short, the uncertainty of Pavese's fencing pedigree does not entirely negate any value that might be obtained from his treatise, but it cannot in good faith be considered representative of any particular lineage or institution until more insight is gained into his early years. What one can do is determine how much his book draws from Parise's material, where he diverges, and if any other possible influences are evident. While a comprehensive comparison would be beyond the present scope, there are a few aspects of the book which I feel are worth highlighting.

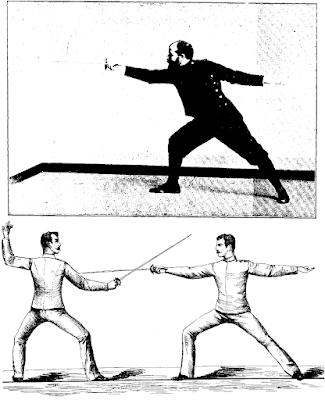

Starting with the foil, the more visually obvious divergences from Parise's method are seen in his guard position, which appears more evenly-weighted rather than Parise's slight rear-weighting, as well as in Pavese's lunge, which is more akin to what's prescribed in northern Italian masters such as Masiello, with a forward lean creating a straight line from left shoulder to left heel, a movement which Pavese explicitly describes as being 'very important'.47

|

| Top: Pavese Bottom: Parise |

Aside from the regular step forward or 'step in advance', Pavese also describes what is commonly known today as the balestra or jump forward, a technique that had only recently started to be described in Italian treatises.48 Also curiously modern is part of his terminology, that being his designation of parry of 1st what was usually referred to in contemporary Italian terminology as 'half-circle' or less commonly 'parry of 5th'. In the Italian school it would be more common later in the 20th century for the term 1st or prima to be used to refer to both the French-style pronated parry and the supinated 'half-circle' parry, but not so in 1905, making Pavese an outlier in this respect.

His sabre section is even more abridged than the foil, with many noteworthy omissions. Both Parise's 'yielding 6th' parry (otherwise known as parry of 7th) as well as his guard of 1st, Parise's preferred engaging guard, are both missing. The exercise molinelli are entirely absent, but he preserves their drawing recovery swing in the individual cuts. He also removes Parise's prescribed obtuse angle between the extended arm and sabre when cutting, instead preferring to maximise reach with a straight line from shoulder to point.

Pavese's unique addition of the 'Form for Articles of Agreement'—a bouting contract seemingly inspired by those used for duels—and the advice he gives about fencing equipment and bouting culture are an admirable attempt by the author to adapt the material for an American audience—that is, one which had far less general cultural awareness of fencing and was accustomed to different public events compared to those in Western Europe. His work gives the impression of a man who was determined to continue promoting the art in spite of the cultural apathy he encountered both before and after the treatise's publication.

Conclusion

The typical approach to understanding a historical figure or event is, essentially, through examining as many reliable sources as possible to determine what happened and why. The challenge that became apparent in writing this article is a good demonstration of how difficult it is to convincingly prove something did not happen. At what point does the absence of evidence become sufficiently overwhelming to conclude that a particular event did not take place, or at least not how another source might claim so?

Through the extensive examination of government records, newspapers, sporting magazines, tournament reports, and military journals, no evidence of Generoso Pavese's fencing career in Italy was found during the period he claims to have been not only active, but renowned to some degree in the Italian fencing scene. Even after arriving in the USA and receiving considerable attention from media institutions around the country, the claims made by and about him were often contradictory, provably false or greatly exaggerated. Although these claims may weave a compelling narrative, they misleadingly depict Pavese as belonging to a particular class of fencing masters whose qualifications made them highly regarded around the world, therefore presenting a tempting opportunity for those willing to exploit this reputation for personal gain.

The method he describes in his treatise cannot be be considered a product of Italy's military fencing master's school due the unreliability of his narrative, but despite this Pavese's treatise remains an interesting example of one person's attempt at propagating the modern Italian school of fencing in the USA before the more successful attempts later in the century.

2 Generoso Pavese, Foil and Sabre Fencing (Baltimore, MD: King Bros., 1905).↩

3 Id., p. 5.↩

4 For the 1905 passport application: National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; Roll #: 669; Volume #: Roll 669 - 01 Feb 1905-28 Feb 1905. Note also that on his death in 1947, some obituaries gave his place of birth as Florence. See "Noted fencer dies at 81," Baltimore Sun, 16 January 1947, 10; "Generoso Pavese," New York Times, 16 January 1947, 25.↩

5 American articles: "With steel blades," New York World, 8 December 1893, 9; "Italy's master of fencing," New York Times, 8 December 1893, 3. Italian articles: Accademie, Tornei e Notizie, Scherma Italiana, 16 November 1893, 84; Accademie, Tornei e Notizie, Scherma Italiana, 1 January 1894, 6–7; Accademie, Tornei e Notizie, Scherma Italiana, 13 January 1894, 12.↩

6 "A mounted sword combat," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 22 February 1894, 8.↩

7 "To cross swords," Brooklyn Citizen, 22 February 1894, 3.↩

8 "Parvese defeats Kendal," New York Daily Tribune, 12 March 1894, 3.↩

9 "Music and fencing," New Haven Daily Morning Journal and Courier, 16 May 1894, 2.↩

10 National Police Gazette, 28 April 1894, 11.↩

11 For his attendance at the fencing master's school: Cesare Francesco Ricotti-Magnani, "N. 90. - Corso speciale presso la scuola magistrale di scherma. - (Segretariato generale). - 27 luglio," Giornale Militare 1885: parte seconda, no. 31 (30 July 1885): 340–1. It is also likely Sfrisi took part in the last course to be held at the Milan master's school before its closure, as mentioned in Cesare Francesco Ricotti-Magnani, "CIRCOLARE N. 73. - Ammissione di sottufficiali ad un corso speciale presso la scuola magistrale di scherma. - (Segretariato generale). - 20 giugno," Giornale Militare 1885: parte seconda, no. 26 (23 June 1885): 293. For his participation in the Bologna tournament: Carlo Pilla, Torneo nazionale di scherma 3-7 maggio (Bologna: Società tipografica già compositori, 1891).↩

12 "He'll teach Roosevelt to fence," New York Sun, 15 February 1903, 8.↩

13 Pavese, Foil and Sabre Fencing, 5.↩

14 Some sporting magazines that covered fencing tournaments are L'Escrime Française for France, Scherma Italiana for Italy, and Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung for Austria. For the 1887 Florence tournament, extensive coverage is found in the Florentine newspaper La Nazione throughout May 1887. For the 1889 Rome tournament, see various articles in large newspapers such as Turin's Gazzetta Piemontese, Milan's Corriere della Sera, and Rome's La Tribuna in November 1889. For the 1891 Bologna tournament, see Pilla, ibid. For the 1891 Venice tournament, a report is found in Baiardo: periodico schermistico bimensile from 8 September 1891.↩

15 "He'll teach Roosevelt to fence," New York Sun, 15 February 1903, 8.↩

16 "Escrime," Le Journal, 24 November 1904, 6.↩

17 "Master of the foil coming to America for matches with Yankee swordsmen," Indianapolis Sun, 11 January 1905, 7.↩

18 L'Auto, 6 January 1905, 1.↩

19 "Rondell's great fight," Boston Globe, evening edition, 25 January 1905, 3.↩

20 "Escrime," L'Auto, 1 April 1905, 5.↩

21 "Sport," Don Chisciottino, 4 June 1905, 3; "Scherma," Il Vaglio, 1 July 1905, 3.↩

22 "Pavese dares Tronchet to fight to the death," San Francisco Call, 6 November 1899, 6; G Pavese, "Pavese will fence Senac," National Police Gazette, 23 March 1901, 11; E. G. Westlake, "Who Is the Fencing Champion of the Western Continent?," Columbus Daily Herald, 27 April 1901, 3.↩

23 "Austin & Stone's," Boston Post, 14 April 1896, 6.↩

24 "Challenged to a duel," New York Times, 26 April 1898, 4.↩

25 "Pavese ready to fight Spaniards," New York Evening Journal, 9 June 1898, 6.↩

26 "Capt. Stahl Challenges Carranza," New York Times, 28 April 1898, 7; "Gen. Lee back in Washington," New York Times, 29 April 1898, 3; "W. D. Ballari wants to Fight Carranza," New York Times, 30 April 1898, 4.↩

27 "Pavese's sword," Mexican Herald, 22 October 1899, 13, extract from Denver Evening Post.↩

28 Parlamento Italiano, "Cesare Ricotti Magnani," viewed 10 February 2022, <https://storia.camera.it/deputato/cesare-ricotti-magnani-18220130/governi>↩

29 "Pavese dares Tronchet to fight to the death," San Francisco Call, 6 November 1899, 6; "Swordsman Pavese In Town," Baltimore Sun, 20 October 1901, 6; "Swordsman Pavese accepts," Baltimore Sun, 20 May 1902, 6; "He'll teach Roosevelt to fence," New York Sun, 15 February 1903, 8; "Fencing bout arranged," Altoona Mirror, 2 March 1909, 6; "Prof Pavese, Teddy's sword master, open for business; want a date?," Tacoma Times, 14 April 1909, 2.↩

30 According to Gelli, less than 2% of duels in Italy from 1 June 1879 to the end of 1889 resulted in death. Jacopo Gelli, Statistica del duello (Milan: Tipografia degli Operai, 1892).↩

31 "He'll teach Roosevelt to fence," New York Sun, 15 February 1903, 8; "Master of the rapier," The Argus, 21 February 1903, 10; "President's skill with foils," Washington Times, 5 October 1904, 7; "Escrime," Le Journal, 24 November 1904, 6; "Roosevelt allievo di un schermidore italiano," Gazzetta dello Sport, 28 November 1904, 2.↩

32 "Prof. Pavese, Teddy's sword master, open for business; want a date?," Detroit Times, 21 April 1909, 4; "An expert swordsman," Waterbury Evening Democrat, 4 May 1899, 4.↩

33 Aside from the passport cited in footnote 5, the only passenger listing I have found so far with containing Pavese's name is on his return in 1905: Year: 1905; Arrival: New York, New York, USA; Microfilm Serial: T715, 1897-1957; Line: 15; Page Number: 64↩

36 "A mounted sword combat," Brooklyn Daily Eagle 22 February 1894, 8; Miscellaneous Sports, New York World, 30 May 1894, 2; "To cross swords," Brooklyn Citizen, 22 February 1894, 3.↩

35 Pavese, Foil and Sabre Fencing, 5.↩

36 "Prof. Pavese and his claims for the Italian school of fencing," The Washington Times, 6 July 1902, 28; "Swordsman Pavese in Town," Baltimore Sun, 20 October 1904, 6.↩

37 "He'll teach Roosevelt to fence," New York Sun, 15 February 1903, 8. An aforementioned article from 1894 also mentions a 'Pessini' as Pavese's master: "To cross swords," Brooklyn Citizen, 22 February 1894, 3. The Baltimore Sun of 21 July 1904 instead claims that Pavese was 'two years riding master at one of the leading cavalry schools of Italy'.↩

38 Cesare Francesco Ricotti-Magnani, "N. 2. - Corsi eventuali presso la scuola magistrale militare di scherma. - (Segretariato generale). - 2 gennaio," Giornale Militare 1885: parte seconda, no. 1 (7 January 1885): 2–3.↩

39 Lists of successful applicants to the Rome fencing master's school during this time may be found in the following issues of the Giornale Militare: 3 October 1884, 7 January 1885, 15 April 1885, 27 July 1885, 4 March 1886, 23 September 1887, 18 August 1887. Some students who were known to have attended the school do not appear in these lists, but they such instances are rare. It must also be noted that the comprehensive directory of military officers contained in the annual yearbook Annuario Militare del Regno d'Italia does not list a Generoso Pavese at any point in the 1880s or 90s.↩

40 Claims of military service: "Noted fencer dies at 81," Baltimore Sun, 16 January 1947, 10; "Generoso Pavese," New York Times, 16 January 1947, 25. For his census entry, see U. S. Federal Census. Year: 1930; Census Place: Baltimore, Maryland; Page: 1B; Enumeration District: 0577; FHL microfilm: 2340591.↩

41 "First Fascist School Opened in Baltimore," Daily Worker, 19 June 1928, 4.↩

42 Biographical details on Marco Piacenti: P. B. [Pietro Baldi], "Marco Piacenti," Gazzetta dello Sport, 18 March 1898, 1; "Le Maitre Piacenti," Les Armes, 5 June 1910, 250. Piacenti's tournament achievements are easily verified by contemporary newspapers and sporting magazines, such as the Italian Scherma Italiana and the Hungarian Sport-Világ. Piacenti was classified in the 1st category in both foil and sabre at the tournaments of Genoa 1892, Venice 1894, Milan 1894, Prague 1895, and Budapest 1896, among many others.↩

43 Marco Piacenti, "Marco Piacenta on fencing," Boston Sunday Post 7 May 1899, 21.↩

44 "Broadsword contest ended in a fizzle," Brooklyn Standard Union, 9 April 1894, 8; "Boxing resumed at Coney," New York Sun, 2 August 1894, 5; "Broadswordsmen in danger," New York Sun, 10 September 1895, 5.↩

45 "Scannapieco Won the Championship," 11 March 1897, 5. This defeat did not go unnoticed by all, however, with the Wilmington Sun commenting on an event of Pavese's in New York the following year: 'Professor Pavese, of New York, who, although easily beaten by Professor Scannapieco, claims the fencing championship of the world ...' (31 March 1898, p. 3).↩

46 "Pavese dares Tronchet to fight to the death," San Francisco Call, 6 November 1899, 6.↩

47 Pavese, Foil and Sabre Fencing, 127.↩

48 Other early examples are found in: Luigi Barbasetti, Das Stossfechten (Vienna: Wilhelm Braumüller, 1900); Primo Tiboldi, La scherma di fioretto (Milan: Casa Editrice Sonzogno, 1905).↩